Algorithm Culture, Cultural Homogeny, and the Importance of Curation

It is generally inaccurate to suggest that the landscape of music is changing. Of course, creative industries are always in a state of change as they are constantly disrupted by an annual slew of new technologies and new audience demands. However, if such a saying is to indicate a transference between an old guard towards something new, perhaps revolutionary, then we are already deep within it. So to is it a direct cause of, and correlation between, those aforementioned factors. Audience research and burgeoning technology, particularly the ways in which one can harness the other, seems to generate cartoonish dollar signs in the eyes of the creative sector’s leading figures.

Frank Zappa, an artist who’s presence in the industry seemed to rupture the status quo of the 60s and 70s alternative with his absurdist brand of psychedelia and jazz, once lamented the music industry’s departure towards safe business decisions over bold, new directions. He viewed a music industry in steep stylistic decline, attributing it to a newfound knowledge of what sells in the market. He yearns for “cigar-chomping, old guys” who possess less than a morsel of musical understanding, but a desire to take advantage of this burgeoning industry of rock ’n’ roll and the next generation of talents that was yet to materialise in the dawn of Western counter-culture. In the pursuit of this, a grizzled executive or two would be happy enough to throw wealth at something with enough of a buzz around it in the hopes that they struck the next hit. It was, more or less, the blindfolded gold miner approach to music production.

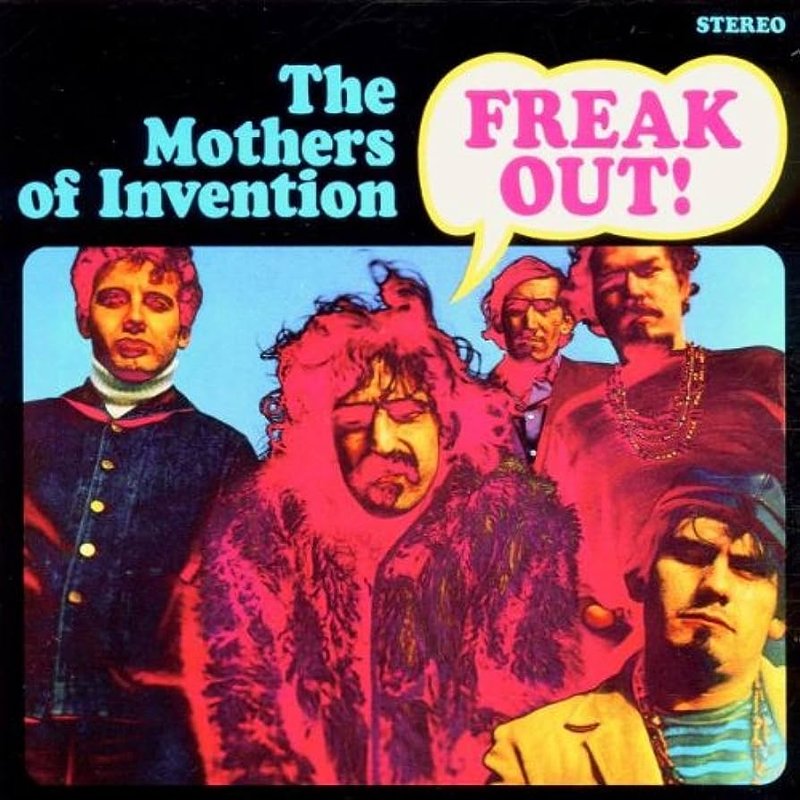

Incidentally, this narrative fits Zappa’s debut record with the Mothers of Invention, Freak Out (1966). The band were taken on under the assumption they were a “white blues band,” and were given an “endless budget” to create the absurdist masterpiece. The record label, unfortunately for them, failed to see many rewards for their gamble. The album made less than a splash in the charts, although notably has gained a reputation as a canonical classic. Regardless, it was good news for Parlophone Records. A year later they were able to release Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Band (1967), the Beatles’ quintessential breakthrough into the concept album and a record which holds Freak Out! as it’s premier inspiration, from the words of Paul McCartney himself.

What Zappa ultimately alludes to here is that the economic naiveté of a music industry approaching the end of the Rock ’n’ Roll mega-boom manifested in a throw-it-at-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks approach that yielded some of the 60s and early 70s more revolutionary works. As the industry learned how to effectively foster talent in the dawn of the Artists and Repetoire Department, homogenisation began to occur. We are left to wonder that if it wasn’t for the culturally inept executive throwing money at a crazed Frank Zappa, high on dissonant cadences and transnational harmonies, would we have ever seen history’s most prolific band’s creative peak?

All the same, the industry learned to observe trends. Minimising financial risk became the name of the game and it was played well.

Now, we have reached the endgame. Algorithm culture has become not only commonplace but more or less the precedent for those looking for success in the creative industries. Most listeners approach music consumption in the form of streaming services such as Spotify or Apple Music, and in these apps algorithmic personalisation is the core principle of the user experience. On Spotify especially, emphasis is on the “your” as opposed to the universal:

- Your top picks

- Made for you

- Your daily mixes

- What your friends are listening to

The move towards a personalised user experience coincides with the rise disruptive rise of Big Data. Big Data is generally understood to include 3 “Vs”: Volume, Velocity, Variety. Volume refers to amount of data available, Velocity the speed to which it is available, and Variety the differing sources from which data comes from. In regard to music streaming, there are two further factors worth considering: machine learning and the digital footprint. The latter refers to the incidental nature of data generation. We, as consumers, generate data every time we play a song on Spotify or add a song to a playlist. Data generated by the user is a complete by-product of activity and remains completely cost-free. Machine learning seeks to identify the trends between user interaction and the qualities of the music played. It is a form of audience research that seems to nullify those that came before as the need for focus groups or surveys become obsolete in the face of immediate, personalised, passively generated music data.

Spotify’s usage of big data can most easily be charted to its acquisition of The Echo Nest in 2014. The service fuels the majority of the streaming company’s personalisation interfaces. The Echo Nest is a service that offers a myriad of descriptive data that varies from easily quantifiable (Tempo, duration, time signature, loudness (in decibels), etcetera), to the more abstract (danceability or energy for instance, which are calculated by formulas unavailable to the general public). Researchers discovered that it was indeed predictive of what would become ‘hit songs’, and the service was integral in the creation of Spotify’s Discover Weekly function. Released in 2015, Discover Weekly promised a personalised playlist featuring new music that was mapped to your listening habits by Echo Nest parameters. Music you hadn’t heard, delivered to you before you knew you wanted it. Suddenly, Spotify had removed the middle man. No longer would Spotify be the place where consumers could listen to the music they wanted to hear, it was now telling the consumer what it ‘needed’ to hear. Music discovery and music consumption were now aligned under one, simple to use, cheap service.

And it worked, flawlessly, at least from a business perspective. It was reported that in the first ten months of Discover Weekly’s introduction that over 10 billion songs were streamed from the service. Perhaps not coincidentally, Spotify broke the billion barrier in annual earnings that same year. In 2016, Daily mixes were launched. Now listeners had their passively generated data laid out in front of them, in the form of neat, genre-separated packages. Perhaps the most successful innovation that Spotify developed for their app was Spotify Wrapped, which launched in 2017. This development, which also utilises data analysis, gathers your listening habits for the year and feeds back the trends and commonalities in your taste, both personally and with those on your friend's list. This includes how much music you consumed in terms of minutes listened to, which genres and artists were among your favourites, and how that compares with the rest of the world or with your friends. Spotify’s motivation behind the feature was to generate “FOMO”, fear-of-missing-out, amongst non-users. It has become a form of cultural currency that appears annually, people celebrate achieving an artist's top 1% of listeners, and this currency can only be achieved if you hold a Spotify membership. It seems that the shift to a personalised experience was a positive change for the company’s customer loyalty and user expansion.

In fact, there is no doubt about it. Digital music has grown to be the second highest source of income for the music industry, surpassed only by live music, a trend that almost directly correlates to the introduction of Spotify in 2010.

The Echo Nest cannot operate on it’s own, however. This expansion was facilitated by artificial intelligence. Human methodologies can only go so far in computing the unfathomable datasets that services like Echo Nest provide. So too are the only getting larger. The branch of AI that we are referring to hear is machine learning, which in the music industry is used in predictive models. This is when AI calculates unknown variables from quantifiable data. For instance, in the music industry, this would be determining what any given user may enjoy (the unknown variable) based on the aesthetic qualities of what said user has already listened to.

The details of these machine learning neural networks are hugely complex and not worth detailing here, but Spotify engineer Fernando Diaz provided a succinct explanation of why they are so useful to Spotify’s personalised model. User needs is central to the philosophy. In some instances, these needs are simple. A simple search for a genre of music, or music that satisfies general needs such as ‘running music’ or ‘study music’ is easily answered by matching this search term to the most popular matches in its database. It is when the requirements become vaguer that further analysis is needed that Spotify must combine its metadata on both user and content understanding. This comes in the form of individual song recommendations such as those found in Discover Weekly, and it is here that neural networks become useful to us

There is a difficult complexity here to address forever, and that is what parameters do we give the AI in order to complete this task. It cannot happen organically. There are objective factors in music that are easy to identify, whether that be the key or BPM amongst other examples, but how do we address the “why” of user data. This is to say, how do we account for social, cultural, and economic factors that influence what people listen to. How does an artificial intelligence reckon with race, gender, class, sexuality, or location? This question offers a fundamental insight into the creation of AI networks. These technologies may be invented to imitate humans, but that is not to say that they are free from human influence. An AI must separate identities based on a programmers cultural choices, and recommend music accordingly. Or, what you can do instead is attempt to make it more linear. Create common denominators. The latter option was favoured.

Regardless of Spotify’s financial success from the shift to a personalised, data-driven model, it has had profoundly negative effects when it comes to the diversification of music listening. It is not the role of executives to become cultural tastemakers, it is the role of executives to deliver profits. We have thus reached the fearful zenith of audience research that Zappa lamented so much. You might even be pleased to know the man didn’t live long enough to see his gripe expand into the dominant model. With audience data gathering automised, the music industry has been able to create common denominators and push them hard. It was found that 1% of Spotify’s entire catalogue makes up roughly 30% of all plays, with a narrow selection of genres represented. So too is this mirrored in some of Spotify’s most popular playlists, featuring predominantly pop. It may not seem like a particularly impressive statistic, but consider the following. African music only occupies 1% of Spotify’s catalogue, and considering that 68% of all Spotify’s plays are in English, with the remaining 32% shared between all other languages, you cannot imagine that the world of African music is enjoying a significant portion of those listens.

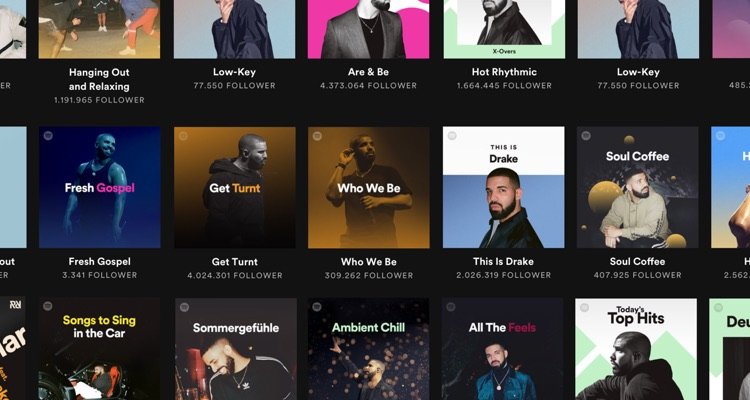

And what of industry gatekeepers? Record labels for instance. Marketing still matters in an algorithmic world. It’s not like Spotify is above advertising. Most will remember the, albeit hilarious, aggressive marketing of Drake’s album Scorpion on Spotify. The service plastered his face across every playlist graphic available including, but not limited too, “ambient chill” and “soul coffee.” At the risk of sounding elitist and protective of the genre, I doubt the Brian Eno and Steve Roach’s of the world would be best pleased about being associated with notorious ambient piece, “Passionfruit.” A great song all the same, but how does this forced inclusion benefit the listener? It is a more than blatant attempt from Spotify to direct traffic. Algorithm culture benefits those with the wallets large enough to break the barrier of entry. Not all artists can afford to promote their albums through one-off in app collaborations, as Taylor Swift recently did with her “Top 5 Eras” functionality. This isn't really even a critique of the artists involved in these marketing stunts, but of Spotify for openly embracing favouritism. I highly doubt Taylor Swift had anything but positive intent in doing this, and it was embraced heartily by fans, to which I truly believe there is nothing wrong with. It has to be asked, however, what the internal politics are that pick and choose who receive these benefits.

And what of geography and language? Considering, as aforementioned, that Spotify’s English speaking catalog makes up the vast majority of plays with nearly a third of total plays being relegated to the same 1% portion of music (predominantly pop), it wouldn’t be amiss to suggest that Spotify is playing into its own hand. Why wouldn’t they? They possess one of the industry’s greatest data sources, the listeners themselves, and are actively reinforcing what they find. Thus forms rigid, unchanging echo chambers.

Spotify is ultimately selling convenience, and convenience seems to be at odds with discovery. Bandcamp is an example of a service that not only supports high artist payouts, but allows for discourse on its platform. Curation is present through daily articles highlighting the importance of various artists, location-based movements, and record labels. It has become a common pilgrimage for artists seeking to escape the thrall of Spotify’s consumer black hole. Legendary indie folk musician spoke of this when releasing his 40-minute epic “Microphones in 2020” a few years ago through his twitter:

“Just because Spotify’s Business model is not illegal yet, that doesn’t make it right. Pay the people who make what you love. It’s very simple… that is, if what you love is vital music made outside the perversions of corporate sponsorship and hyperventilating capitalist hustling.”

For an artist like Elverum, who already exists outwith the perceived mainstream, the uphill battle of existing on a service that already refuses adequate pay and creates a culture where attention is won with money and exposure is simply not worth it. That being said, Elverum can afford to take that leap. He is a western artist with considerable indie credibility. It is certainly easier for an artist who sweeps up endless “Best New Album” accolades on Pitchfork or half a million views on raving Anthony Fantano videos to be content with departing the exposure of Spotify. Quite simply, his fans will follow him there. I sit beside my record player, proudly displaying my vinyl copy of “Micropones in 2020” that I bought for just under fifty pound on band camp (my album of the year, incidentally). That’s not to discredit Elverum, an unabashed master, and his views or struggles within the post-digital industry, but it’s obvious which demographics this structure harms the most: non-western artists, economically poorer geographical zones, and genres outwith the western canon of acceptance. Ultimately, though, the brutal truth is that the promise of curation and discovery is not enough to sway fans, the vast majority of whom likely have a very casual relationship with music, to alternative sources.

So it seems that we are at an impasse. Spotify has no reason to depart from its algorithm culture, record labels have no reason to stop generating content directly for algorithm culture, and listeners are not likely to part with the service. Furthermore, why should fans part with convenience? This latter point is one of particular contention.

To switch mediums for a moment, the world of film has seen a similar clash of consumption approaches. In a series of op-eds for various publications, all of which seems to fuel social media’s fire for unproductive or reactive discourse with an especially potent brand of gasoline, Scorsese lambasted the film industry’s switch to viewing film as “content” as opposed to culturally potent objects. The target of his ire is two-fold, the brutal commercialisation of film by franchise such as Marvel as well as algorithm culture. Both are interrelated, aiming at uncovering the devaluation of art in favour of entertainment. The blurred line (if such a line even exists) is long debated and this post does not have the scope to tackle it, but all the same Scorsese’s views are best encapsulated by the passage following from Harpar’s Bazaar:

“If further viewing is “suggested” by algorithms based on what you’ve already seen, and the suggestions are based only on subject matter or genre, then what does that do to the art of cinema?

Curating isn’t undemocratic or “elitist,” a term that is now used so often that it’s become meaningless. It’s an act of generosity—you’re sharing what you love and what has inspired you. (The best streaming platforms, such as the Criterion Channel and MUBI and traditional outlets such as TCM, are based on curating—they’re actually curated.) Algorithms, by definition, are based on calculations that treat the viewer as a consumer and nothing else.”

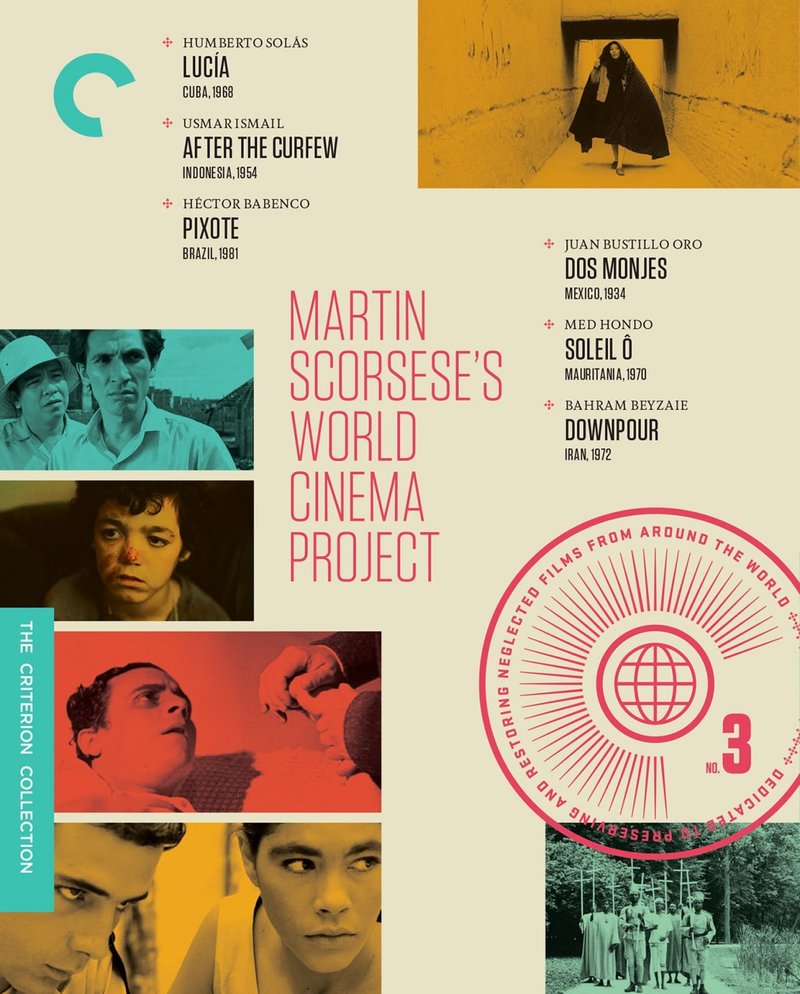

He also praises the risks taken by early distributors such as Amos Vogel, Grove Press, and Dan Talbot for bringing foreign cinema to western regions. To him this was not just a charitable act, but one of bravery, betting on world cinema and it’s differing aesthetics as one that can captivate general english-speaking audiences. Scorsese himself is a leading example of this. His World Cinema Project seeks to regularly restore world cinema into HD and re-release them through distributors such as Criterion. Cinema that would likely be lost over time had he not done so. This is an act of cultural preservation, distribution IS cultural preservation, and to call such an act elitist is to say that these films are not worthy of circulation. In a market dominated by 100 million+ dollar budgets, those that usually only Western outlets can regularly supply, this is unquestionably a supremacist statement (knowingly or not). Realistically, it likely comes from a place of insecurity. The need to be curated to likely inherently implies a “holier-than-thou” attitude, and those who enjoy art as casual entertainment are likely feeling demeaned by it. Still though, blind acceptance of these practices nonetheless upholds these institutions.

The presentation is different, but the sentiment is the same, Scorsese and Zappa wanted those with the resources to present art to an audience to take a chance on new, radical art. If we do not support cultural efforts to share vibrant, diverse art in protest of algorithm-enforced homogeneity, then it will be overwhelmed. Most of these efforts are fringe, grassroots, or voluntary (like us here at Subcity Radio) but it may be all we have until cultural policy changes. Here at Subcity Radio we support editorial freedom, represented by a diverse and passionate group of contributors, who’s various shows are evidence enough of true curation’s ability to portray a vast selection of great music. A lot of which, you may not have heard otherwise. It is an essential labour to ensure the survival of international and fringe art. It is ultimately a battle of global and cultural inequality, represented through the consumption choices we make and the systems we help uphold as music listeners. Even on the level of community radio.

In future editions of the blog, we may look to address further the importance of curation, as well as some of the cultural policy changes we could make on an industry level to help circumvent some of these issues, but for now we will end here. Curation will always be relevant to the preservation and circulation of great art that algorithm culture otherwise rejects. It is a noble act to be partaking in that, however large or small. With Spotify now having rolled out its AI DJ, an artificial "curator" which is merely a representation of it's already existing features with a shiny new coat of radio-esque paint, this discussion is more relevant than ever in the face of this ever improving technology.

By Cam Young

listen back

listen back